VEGETABLE LIFE OF THE TROPICS

A. Hyatt Verrill

Popular Science; Aug 1, 1898; Researched by Alan Schenker, digitized by Doug Frizzle, Sept. 2011.

To a person accustomed only to our northern woods, the tropical forests are a source of constant marvels, and something new and strange is encountered on every hand. In the first place, whereas our New England woods are thick, and the ground usually covered with underbrush, the woodland of the tropics as a general rule has little or no small growth, with the exception of scattered palmettos. The trees are heavily festooned with a perfect network of vines, or "lianas," of all sizes, some delicate as thread, others a foot or more in diameter. The trees themselves are veritable giants, frequently attaining a height of over 200 feet, without a branch or twig, for a hundred feet from the earth. The trunks, instead of being round and gently tapered, have their bases flattened into huge, slab-like buttresses or hips, which sometimes extend outward for 30 or 40 feet.

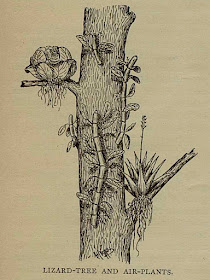

On the vines and branches are an endless number and variety of air-plants and orchids, both beautiful and curious. Among the most peculiar of these and one that will invariably excite the wonder of the observer is the Lizard-tree, while the so called Wild-pine, is one of the most useful of wild tropical vegetables. The Wild-pine, in appearance, resembles the top of a common pineapple, with broader, softer and smoother leaves. At the base of each leaf is a cup-shaped cavity which always contains fresh, cool water, and in several instances this tiny reservoir has been known to save the lives of travellers dying of thirst.

The Lizard-tree, when growing, looks something like a huge, green, lizard crawling up the tree-trunk, hence its name, though for my part I think Centipede-tree would have been far more appropriate. It consists of a jointed, bamboolike stick, or stalk, with smooth, oval leaves growing directly from the bark, and with slender, white roots springing from each joint. Its peculiarity lies in the fact that the joints break off of their own accord, and falling to the ground or on branches of trees, immediately begin to grow, clinging on by their delicate rootlets. After the new plant has attained a length of 3 or 4 feet, the lower sections again drop off and start life in a new place. When falling on the ground, however, the plant continues to grow in length until some convenient tree is reached, when it immediately fastens to the trunk and breaks away from the main stalk. The portion holding on the tree continues its growth upward. In this manner the Lizard-tree spreads very rapidly and the numerous, jointed pieces of various lengths, holding fast to the tree-trunks and branches, at all heights from the ground, present a very odd appearance.

Another huge air-plant, very common in the West Indies, looks much like a cabbage. The seeds of this plant are enclosed within a cup-shaped capsule deep within the center of the leaves. The roots are slender and when the plant attains its full size, it becomes top-heavy, so that, at the first hard wind or heavy shower, it almost invariably capsizes, thus dropping out the seeds.

Among the commonest of West Indian trees, is a large and beautiful one with thick, glossy, foliage growing in a very regular pyramidal shape. This is the "sand-box tree." The seeds of this tree are large, round and nearly flat, enclosed in a pretty scalloped capsule 3 or 4 inches in diameter. These capsules are veritable vegetable pistols, for when ripe and dry, they explode with a loud report, scattering their contained seeds in every direction; indeed, the force of the explosion is so great that I have known one of them to shatter a wooden cigar-box in which it had been placed. The natives of the West Indies use these seed-cases for paperweights. Gathering them before they become fully ripe, they fill the inside with melted lead, which serves the double purpose of giving them the required weight and at the same time preventing their bursting.

The traveller in Central American forests may now and again be surprised at finding what at first sight appear to be rusty cannon-balls lying in the woods. Although they are fully as round, hard and almost as heavy, as the real article, yet they are in reality nothing but the fruit of a forest tree, known to the natives by the very appropriate name of Cannon-ball tree. Within their hard exterior are a number of small, hard shelled nuts, or seeds, of a very pleasant flavor.

We have all seen and eaten those delicious nuts known as Brazil-nuts, but comparatively few people know how they grow. The Brazil-nuts are not borne singly, or in small clusters, as walnuts or chestnuts, but in large numbers, packed closely together within a hard and nearly spherical shell, much like that of the Cannon-ball tree. These cases make very amusing puzzles when a hole is cut in one side. Through this aperture the nuts may be readily extracted, but try as you will, it is next to impossible to get them all back again. Strangely enough, Brazil was so named from the fact of the nuts occurring there, instead of the nuts being named for the country as one would naturally expect.

No comments:

Post a Comment