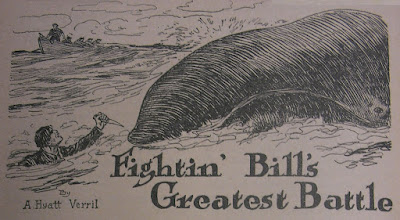

Fightin’ Bill’s Greatest Battle

By A. Hyatt Verrill

From Sea Stories Magazine, August 1924. Digitized by Philip Bolton, Jr. and Doug Frizzle March 2010.

In Numberless battles Cap’n Bill Haven had made good his boast that he could lick anything he met. Then he was compelled to do battle with a sort of antagonist that one ordinarily encounters in a nightmare.

Captain Bill Haven took his coat and hat from the grinning boat-steerer, slipped the former on, placed the natty hat jauntily on his head, flecked a speck from his neatly creased trousers, and adjusted his slightly disarranged collar and bow tie. Stepping to the rail, he retrieved his half-smoked cigar from where he had wedged it in a deadeye, clamped it firmly in his teeth, and struck a match.

"By Godfrey!" he ejaculated, as he blew a cloud of smoke from his nostrils. ''Didn't I tell you I could lick any man whatever stood on two feet? Yes, by Godfrey! I ain't never met nothin I couldn't lick."

"I reckon you did." grumbled the second mate, as he rose groggily to his feet and ruefully felt of a bruised cheek and blackened eye. "And I ain't one to say I ain't licked when I be. And I reckon maybe you ain't come across nothin’ you can't lick—yet." Stepping to the port rail, he spat a broken front tooth into the calm sea. "I'm not one to hold no ill feelin's for getting’ licked fair and square. Just the same. I bet my lay 'gainst a plug of tobaccy you'll run foul of a lickin' yet, cap'n, and I'm only hopin' the Lord'll spare me to be there when you do."

Captain Bill looked over the battered and disheveled officer with a quizzical expression in his mild brown eyes. A half-pitying, half-supercilious smile showed upon his lips, beneath the closely cropped gray mustache.

"I hope you be," he replied in his low-toned, even voice. "But till then, Mr. Mate, just remember if there's any lickin' to be done aboard this ship, Captain Bill Haven's right here on hand for to do it." Turning on his heel, he strode aft, cigar cocked upward, hat brim drawn down, hands in pockets and humming an air woefully out of tune.

"Reg’lar little bantam cock." rumbled a burly Seaman who stood near.

"Many a bantam’ll lick the liver ‘n lights outen a dumb big Plymouth Rock,” observed the cooper with a meaning glance at the form of the second mate who was limping aft. "An’ ye ain't seed half of what Fightin' Bill can do if he puts his mind to it. No, by glory! Not a half on it."

“Wasn't even mussed up a mite," said another, admiringly. "An' mate never even touched him."

"Quicker’n greased lightnin', I’ll say," declared a long, lean down-easter.

“An' ye could ‘a’ heard them cracks he landed a cable's length away. Sounded like the slattin' of a loosed torpsail in a half gale."

Still discussing the recent battle upon the deck, the men slouched forward. To the green hands, the landsmen who had signed on for the cruise on the whaleship Endeavor under Captain Haven, the spectacle of the skipper engaging the second officer in fistic combat on the main deck in full view of the crew was an amazing experience. Small as was their knowledge of ships and the sea, they always had imagined that captain and mates stood together and took equal pleasure in beating up the men, if they beat any one. Yet here, before their wondering eyes, all these ideas had been shattered the third day after leaving New London.

The second mate, Mr. Baxter, had ordered the greenies into the rigging for their first "breaking in," and when one of their member, a pale-faced, frightened-eyed young fellow, had hesitated to obey, the officer had leaped at him with clenched fists and had promptly knocked the cowering lad into the scuppers. Before he could rise the mate had lifted his heavily shod foot, but before the vicious and cowardly kick could be dealt there was a commanding bellow from the little skipper.

"Belay that!" he had roared in a voice out of all proportion to his size, drudgingly the second mate had lowered his boot and turned away from his victim to see Captain Bill sauntering nonchalahtly toward him.

“Guess you don't know the rules on this ship, Mr. Baxter," he had remarked in even tones as he drew near. “If there's any beatin' up to be done you can just call on me. Yes, by Godfrey, there ain't but one cap'n on my ship and that cap'n can do all the lickin’ that’s to be done. And," he had added, as he stripped off his coat and removed his hat and handed them to a boatsteerer “seein’ how you're so all-fired fond of usin' your fists, I'm a goin' to give you a chance to use 'em. I ain't never met nothin' I can't lick yet, and when I do I'll turn the ship over to the one that licks me."

Mr. Baxter had stared at the little skipper incredulously. Most amazing events were occurring in far too rapid sequence for his mind to grasp them. Who had ever heard of a whaleship captain objecting to a mate hazing a greenie? Who had ever heard of a captain "putting the iron" into an officer in the presence of the crew? And who, in all the annals of the sea, had ever heard of a captain fighting with an officer of his ship?

Mr. Baxter certainly had not, though, had he put the questions to the old hands, there would have been a unanimous response of "aye" from a dozen hairy throats, for every whaleman of New London knew of Fightin' Bill Haven's idiosyncrasies and scrapping ability. But, most unluckily for Mr. Baxter, he was a Nantucket man and Captain Bill's peculiar methods and fistic prowess were wholly unknown to the islanders, save among a few of the whalemen who at one time or another, had shipped on New London vessels that Captain Bill would rather fight a square, clean fight than eat, or even smoke for that matter; that it was his boast that he had never yet met his match; that no Connecticut whaleman ever dreamed of questioning this or of testing Bill Haven's prowess, and that one of Skipper Bill's strictest rules was that there should be no beating or abuse of men aboard his ship, were all matters of which Mr. Baxter was woefully ignorant.

But he had been far from unwilling to enter a good mix-up himself. He was a powerful, heavily built young fellow, naturally sullen, bad tempered, and ready with fist or boot, and he prided himself on being a fighter and a hard nut to crack. As he had glared, half wondering and half contemptuously at the captain of the Endeavor an ugly grin spread over his sun-burned, heavy-jawed face. It might be contrary to all precedents and customs for a skipper to fight with an officer, but if the captain wanted to fight, why, he was the lad to accommodate him. The very thought of the little skipper having a show against him had brought a chuckle to his lips. But Baxter was cautious. Like all Nantucket men, he had the greatest hatred and contempt for the mainland whalemen or “off-islanders” and he was quite aware that the feeling was mutual. Was it not possible, he had thought, that this was a scheme on the captain’s part to break him?

“I ain’t no dumb fool,” he had ejaculated, putting his thoughts into words, “Think I’ll say somethin’ or raise a hand to you so you can break me, eh?”

Captain Bill had smiled, stepped to the rail and carefully placed his half-smoked cigar in a safe spot. “By Godfrey, you must think I am a damn island cap’n,” he had retorted a bit hotly. “No, Mr. Mate, if you don’t fight I’ll break you, by Godfrey! This ship ain't no place for men that’s afraid to fight.”

"Afraid!” Baxter roared, stripping off his coat and baring his huge, knotted arms. “I’ll show you who’s afraid.”

Hunching his shoulders, his hairy fists doubled, he had leaped at the little man standing with his hands by his sides before him.

What happened next Baxter could never tell. Even the watching men could not coherently explain.

The skipper’s hands had flashed up and out like lightning, resounding cracks came thick and fast, and with reeling head, feeling as though his face had come into contact with a whale’s flukes, utterly amazed and beaten, the mate had found himself sprawled upon the deck as the captain, unruffled, composed, and as calm as ever, turned toward the boatsteerer and reached for his coat and hat.

It was all an old story to the griming chief mate on the quarter deck, to the tarry old sailmaker, the grizzled cooper and the boatsteerers. Never had Fightin’ Cap’n Bill met his match, never been as much as bruised or scratched, and the New London whalemen had come to look upon him as something almost superhuman when it came to fighting.

Captain Bill, however, had found that his reputation had its drawbacks. No New London whalemen would dream of standing against him, and it was not always easy to find an excuse for picking a good fight with a stranger. He had felt that unless he could find combatants he would grow stale, and had hit upon the plan of making it a rule to fight any officer who attempted to beat up a man on his ship. If the officers were New Londoners they were far to wise to try it, but luck and a scarcity of mates in the Connecticut port often threw a stranger in Skipper Bill’s way. Whaling mates —unless wise to Captain Haven’s methods —were sure to haze the greenies sooner or later, and thus afford the little skipper an opportunity of indulging in his favourite pastime.

Not that Captain Bill was either a brutal man or an ugly one. He was, in fact, the mildest manner of men, and even the most surly and disgruntled member of his crews had never complained that he got more than his just deserts at the hands of Captain Bill. And never had he taken an unfair advantage. Never had he struck a man when he was down, never had he used feet, nails or teeth. To him a fair fight was a delight, a stimulant and a game, and his method of fighting was the strangest thing of all. No man had ever seen him clench his fist, no one had ever seen him deliver a short-arm jab, a punch straight from the shoulder, or a hook. Instead, he held his hands open, dangling loosely at the ends of his arms, and with a movement too rapid for the eye to follow, flicked them right or left, avoiding his antagonist’s blows by ducking and dodging. But those long and bony fingers were far worse weapons than any ordinary man's fists. They could strike with the force of a flail, could raise a welt like that of a tarred rope's end, and could knock a man out as easily as the blow of a belaying pin.

"Ye're dumb-gasted lucky," was the chief officer's comment to Mr. Baxter, as, the skipper having gone below, the second mate appeared on deck with swollen and plastered face. "I've seed him lay a man out cold with one crack of them fingers of hisn. Guess he was a leetle easy with ye, knowin' ye was a Nantucketer."

Mr. Baxter turned savagely on the other. "Stow that!" he growled through his puffed-up lips. "Just 'cause the Old Man got me by dumb luck don't give you no call for talkin' 'bout it. And, by Judas! You can't lick me, even, if that dumb little sculpin did.”

Mr. Geer, the first mate, grinned. “Better ease off a mite on that talk," he advised. ''And I can tell ye right now I ain’t aimin’ to prove to ye that I can lick ye. I know I can, but I ain't calc'latin' to get into no mix-up with the cap'n by provin' it to ye. Guess ye heard him say as how any fightin’ on this ship'd be done by him, eh?”

Baxter snarled an unintelligible reply, muttered an oath under his breath, and stamped forward.

“Bad egg," was Mr. Geer's mental comment, as he watched Mr. Baxter depart. "Got it in for the Old Man an' me all right. Reckon Cap'n Bill should oughta give him a leetle more medicine, maybe.

But if the second mate "had it in" for his superiors, he gave no outward signs of resentment, he was respectful and quiet, and though he seldom conversed freely or in friendly fashion with the skipper and mate, still, being of a taciturn nature, this was taken as being but natural. Apparently, too, the short but decisive battle with the captain had taught him a wholesome lesson. He never attempted to bully or abuse the men, and throughout the "breaking in" of the green hands he used no stronger or more forcible means of persuasion than oaths and most uncomplimentary appelations, most of which it must be admitted were richly deserved and thoroughly appropriate, for, aside from the three or four old whalemen aboard the Endeavor, the crew of the ship was about as tough an assortment of bums and scallawags as the gutters and parks of coastwise towns could produce.

The men, however, were obedient as a whole, and seemed to get on well enough with the second mate. In fact, Captain Bill confided to Mr. Geer that he thought Mr. Baxter was a little too chummy with the men.

"Only way to handle a bunch of whalemen is to make 'em toe the chalk line and keep their place," he declared. "Soon's ever a officer gets a mite human to 'em there's li'ble to be ructions.

"Don't guess Mr. Baxter's over friendly with 'em," replied the mate. "But he kinder feels he got in bad with you to start with, an' I reckon he sort of wants to square himself with the hands.”

"Mebbe," agreed the skipper. “And I ain't lookin' for trouble. Just the same, by Godfrey! if any one wants to start trouble I’m a standin' here ready for to meet ‘em halfway.”

But there was neither sign nor reason to fear trouble. The Endeavor seemed an unusually happy and peaceful ship, and, as luck favored and within three weeks after leaving port she had taken two sperm whales and had stowed down nearly two hundred barrels of oil, every one appeared to be in the best of spirits. Baxter, too, proved that he was a splendid whaleman. He had gone in on the first whale, had got fast and had made the kill like a veteran, and had handled his boat's crew with a masterly skill that had even won a word of approval from Captain Bill.

By the time the ship was off the Brazilian coast, the little incident of Baxter's fight with the skipper had been quite forgotten, at least by all save the second mate. But in his mind it still rankled. To be manhandled and beaten before the men was bad enough; but to be beaten by a little five-foot wisp of a man like Captain Bill Haven, and an off islander at that, was an insult and a disgrace which he could never forgive. Whenever he thought of it his blood fairly boiled and he vowed to even scores with this little skipper, not forgetting the good-natured mate.

Just how or when he would accomplish his revenge were matters that were a bit hazy in his mind. He had no intention of attempting to square accounts single-handed, and, being an officer, he was loath to plot with any of the men forward. The cooper, blacksmith, sailmaker, and boatsteerers were all men who had sailed with Captain Bill and Mr. Geer before, and were not, Baxter knew, the sort to aid him in any scheme he might hatch out.

But in the half-caste kanaka steward he found a sympathetic friend. Joe, the steward, bore every earmark of an in-and-out rascal. His mouth was twisted to one side by an ugly scar across one cheek; his left eye was fixed in a perpetual leer from another scar, and his yellow skin was hideous with the pits of smallpox. Why Captain Bill ever employed him was something of a surprise to all the skipper's acquaintances, for Joe had won a far from enviable reputation among the whalemen. Two vessels on which he had sailed had come to unlucky ends; one going down in mid-Ocean leaving Joe the sole survivor; the other going on the rocks of a mid-Pacific island where, according to the kanaka, every member of the ship's company but himself and a follow native had been murdered by cannibals, the two kanakas being spared because of their kinship with the savages. There was, to be sure, no proof that the steward had any connection with these disasters. But old captains shook their heads and pointed out that Joe's record on many a log included flogging for mutinous behavior and confinement in irons for disobedience, and that the captain of one bark on which he had served had died at sea soon after Joe had been disciplined.

But there was no denying that the ugly-faced rascal was a most excellent steward. Captain Bill boastfully declared that he'd like to see the kanaka or white man or black that he couldn't keep in hand, and he reminded his friends that he was hiring Joe for a steward and not for his looks or his character. So far, Joe had been beyond criticism, he had been respectful, willing, and had thoroughly borne out his reputation as a master steward.

But Baxter soon found that the kanaka secretly hated Mr. Geer, as he himself hated the skipper, and in his hatred for the mate he included Captain Bill, just as in his own mind he included the first mate in his hatred of the captain. Just why Joe held a grudge against Mr. Geer, the second officer could not discover for some time. Then one day Joe confided that on a previous voyage, when Mr. Geer was third mate of the brig Constance, he had caught the steward stealing liquor from the cabin stores and had administered a deserved and thoroughly sound thrashing on the spot.

So, the two having a common cause for resentment against the after guard, they became quite chummy and spent a deal of time, while the ship cruised back and forth across the south Atlantic, in trying to hatch some scheme which, while quite safe for themselves, would bring disaster or misfortune upon master and mate.

But it is one thing to plot and quite another thing to materialize trouble on a whaleship. Whalemen are not the stuff of which mutineers are made as a rule, and while fearful and bloody mutinies have occurred on whaleships, mutiny of a serious nature is a rare occurrence. The majority of the men, though worthless guttersnipes ashore, are born cowards, and there is always a feeling of distrust for one another among them. Moreover, the boat-steerers and other petty officers are usually faithful, honest men, and there is neither the organization, the brains nor the leadership among the rank and file of the hands to either plan or carry out a mutiny that amounts to anything. But, given a leader, given the least excuse for trouble, and the ignorant, tough foremast hands are tinder that will flame into murderous rebellion at the slightest spark of provocation, regardless of consequences.

But on the Endeavor neither the villainous kanaka nor the surly, hatred-nurturing second mate could find any excuse for using the men as tools for their nefarious schemes.

Not until the ship was far south and cruising between Tristan da Acunha and the Falklands did the least trouble or dissatisfaction arise.

At the Cape Verdes the ship had taken on stores and provisions—fresh vegetables, fruits and several crates of fowls—and now, for ten days in succession, the daily menu had included chicken. Why men who were accustomed to salt beef and pork should object to fowl, even though the birds were a bit ancient and tough, is something of a mystery, but object they did, and after growling among themselves, drew lots and sent the drawee of the shortest chip aft as a deputation to state their case to the skipper.

Captain Bill listened with undisguised amazement in his big brown eyes as the hulking fellow announced that he and his mates were tired of "buzzard” and demanded a change of diet. Then he exploded.

"By Godfrey!” he ejaculated, snapping his bony fingers against the skylight with a report like a pistol. "Turn up your noses at chicken, will you! Dod gast your dumb-rotted hides. I'll learn you to eat 'em. Get aloft there you cock-eyed whale louse! Get out astraddle of that there port to’gallant yard-arm and crow like a rooster till I tell you to stop!"

For a moment the man hesitated. With an oath, Captain Bill started toward him, grim determination on his face, and the man lost no more time in obeying. Up the rigging he scrambled, out on the swaying to’gallant yard he clawed his way, and to the accompaniment of roars of merriment from Mr. Geer and the boatsteerers, he began lustily crowing to the best of his ability. But even with this Captain Bill was not yet satisfied.

"Get the men aft,” he ordered the first mate. "Every Jack of 'em.”

Hesitatingly, not knowing what to expect, the men slouched aft.

"So you don't like chicken, eh?" exclaimed the skipper, as the men stood waiting abaft the mainmast.

There was an unintelligible growl from the men.

"H’m, seems like I don't get no answer,” observed Captain Bill. "Reckon we'll have to put it to a vote. All them as don't like chicken, stick up their right hands."

Almost involuntarily, not yet fully realizing what the skipper had in mind, four of the men elevated their hands.

"Four more roosters, by Godfrey!” cried the captain. "Up aloft with them, Mr. Geer, one to the sta'b'd main to'gallant yardarm, two to the fore to’gallant and fourth one to the mizzen crosstrees. And"—to the surprised and discomfited men— "see you keep a-crowin', fit to bust your dumb lungs or, by Godfrey! I'll put every dumb one o' ye in a chicken coop and lash 'em to the boatskids, an' feed ye dry corn an' water, s'help me Judas!"

Five minutes later, the four men had joined their fellow aloft, and across the heaving sea drifted five raucous cock-a-doodle-doos without cessation. If one of the unfortunate five stopped overlong to take breath, a bellow from the skipper, accompanied by dire threats, brought a lusty crow from the delinquent. Not content with the roosterlike sounds emitted by the five, Captain Bill ordered them to make their imitations more realistic by flapping their "wings" each time they crowed. Never had a stranger or more ludicrous scene been witnessed on a whaleship as the five men, balancing themselves precariously on the swaying yards, waved their arms and crowed until their muscles ached and their throats were dry and their voices cracked.

How long the novel form of punishment might have been continued, had not fate intervened, no one can say. But half an hour after the first man had been sent aloft, a whale was raised and the five human roosters were ordered down from their perches to help man the boats.

Captain Bill's methods of adjusting appetites to suit conditions had been thoroughly efficacious, however, and no further objections to a monotonous chicken, diet were heard. No doubt the men would have taken imprisonment, a flogging or almost any other form of punishment and would have forgotten it overnight. But nothing hurts so much as ridicule, the feeling that one has been made the laughingstock of one's fellows, and the five men who had been so ignominiously disciplined would willingly have done murder to even scores with Captain Bill.

Joe realized this. He maliciously and cleverly urged them on and sympathized with them, and, that night, had a long and secret conference with Baxter. Absolutely unsuspicious, entirely ignorant of the mutiny being hatched forward, Captain Bill and Mr. Geer chuckled together over the memory of the crowing men aloft, while the ship drew nearer and nearer to the stormy waters and treacherous coasts of the southernmost tip of South America.

Then one day, as Captain Bill and the two mates stood anxiously peering through the murk toward the rock-bound, wave-lashed land whose exact location was problematical, Mr. Baxter muttered something and hurried below. Presently his shout came from the companionway.

"Something blame funny about this chart, captain," he cried. "Wish you'd step down and have a squint at it."

As the skipper turned to go below, Joe appeared at his galley door with a pot of steaming coffee and came aft, evidently to serve the officers. With a muttered oath, the captain vanished down the companion way.

As he entered the cabin, Mr. Baxter was bending over a chart spread upon the table. Without looking up, he beckoned the captain to him.

"Here 'tis," he said, as the skipper reached the table and glanced at the chart. "'Cordin' to this here—"

Captain Bill leaned forward, peering intently at the spot indicated by the second mate's finger. Instantly the other hurled himself upon the little man, and Captain Bill staggered back. The attack had happened so quickly, so utterly unexpectedly that there was no chance to recover, no opportunity to strike. But Captain Bill’s mind was as lightning quick as his muscles. Even as he reeled back, as he felt himself being borne down, his left hand shot out and his long fingers seized the collar of his antagonist's coat. With a jerk, he pulled himself up, recovered his balance and bumped with such force against the other that Baxter staggered back against the table. At the same instant Captain Bill heard a muffled cry from the deck, the sound of a scuffle and the thud of a falling body. Well he knew what it meant. Mr. Geer had been overpowered or killed; open mutiny had broken out.

But it was no time to think of others. He had plenty to do to look after himself. A knife flashed in Baxter's hand, but he was at too close quarters to use the weapon. With a sudden shove, Captain Bill released his hold of the other, forced him backward against the table edge and struck with that flicking, snapping blow of his open hand. With a hoarse cry of pain the second mate collapsed, his cheek laid open to the bone where the skipper's fingers had struck, blood pouring from the wound, and his head reeling. Before the captain could turn, footsteps sounded behind him, there was a hoarse, savage cry, and an arm was flung about his neck garroting him.

Quick as a flash, the little skipper's elbow shot back viciously. It struck full in his unseen assailant's stomach, there was a gurgling grunt, and as the arm about the captain's neck relaxed, the steward fell moaning to the floor.

By now Baxter had recovered himself. With a bellow like a mad bull, he sprang at the skipper with upraised knife. For the first time in his life, Fightin’ Bill forgot all rules of the ring and used his foot. It caught Baxter in the pit of the stomach, the knife flew from his hand, and, pitching forward, he fell writhing and helpless beside the moaning kanaka. Captain Bill did not stop for more. Sounds of rushing feet and hoarse cries came from above. Dashing up the companionway and slamming the door, he sprang on deck.

Mr. Geer was lying motionless beside the wheel, one of the boatsteerers was stretched beside the skylight, and two others were being forced back as they impotently faced the mutineers swarming along the deck.

Captain Bill was unarmed, the boatsteerers’ only weapons were handspikes, and the mutineers were flourishing spades, lances, hatchets and knives. But the captain never hesitated. Seizing a belaying pin, he leaped over the skylight and hurled himself upon the murderous crowd of men. A single stroke of a spade, the thrust of a lance or knife, the blow of a hatchet or even a handspike, would have ended Fightin' Bill's career then and there. Hut blow or thrust never fell. The sight of the little skipper, of the upraised belaying pin, of the blazing brown eyes and set jaws; the fact that Fightin' Bill survived, that Joe and Baxter had failed; that they were without leaders; and most of all, perhaps, the inborn fear and respect for authority, all combined to cow the mob. They faltered. Then, casting aside weapons, they turned tail and scurried forward, with Captain Bill at their heels. Down the forecastle companion they dashed, crowding, tumbling over one another, thinking only to escape the furious little man racing after them.

As the last of the men disappeared below, Captain Bill was within striking distance. His belaying pin thudded upon the vanishing head of the hindmost mutineer, and, without stopping to use the steps, the skipper dropped like a descending meteor into the crowded forecastle. The men had not the time to scatter. Milling and pushing, they were packed in a dense mass, and Captain Bill landed upon their heads and shoulders. Like a maddened, fighting wildcat, he struck with hands, belaying pin, feet, at everything within reach. Groans, blows, shouts, curses, cries, oaths rose from below, as the boatsteerers and cooper came hurrying to their captain's aid.

But Fightin' Bill needed no help. As the faithful men peered into the dimly lit forecastle their jaws dropped and their eyes widened in utter incredulous amazement. Panting a bit, somewhat disheveled, but quite composed, Captain Bill stood upon the prostrate body of an unconscious man, surrounded by a veritable heap of battered and bruised foes. While cowering in corners, slinking back in their bunks, even on their knees, the survivors were begging for mercy. Alone, single-handed, armed only with a wooden belaying pin, Fightin’ Bill Haven had conquered twenty-one men, And when tally was taken, only ten of the number were fit for duty.

“By Godfrey! It takes an all-fired lot to teach you bums that I'm the only man aboard this here ship to do any lickin’.” was Captain Bill's only comment, as he regained the deck and surveyed his handiwork.

Fortunately, there had been no fatalities. Baxter, all the fight and rascality taken out of him, was bandaged and heavily ironed. Joe, the kanaka, was treated to the most thorough flogging any member of the crew had ever witnessed and declared he was reformed for all time, and the crew, Captain Bill decided after due consideration, had been punished enough. Mr. Geer recovered, little the worse for his experience. He explained how Joe had blinded him by dashing hot coffee in his face, and had knocked him senseless. The two injured boatsteerers suffered nothing worse than flesh wounds and a broken arm.

Altogether, the mutiny had been quelled with no serious results, and Captain Bill had no fears of its breaking out again. The men had been completely cowed. They realized that their skipper was more than a match for them. They had lost all faith in either Baxter or Joe and, like all rough characters, they admired and respected Captain Bill for his prowess and ability to take care of himself and for the drubbing he had given them.

Joe, as he squirmed each time he moved and the welts from the rope's end reminded him vividly of his misdeeds, was thoroughly repentant. He knew he had gotten off very lightly, considering that he might have been justifiably hanged to the yardarm, and like the half savage he was, he regarded the skipper with reverence akin to worship, and could not do enough to show his devotion.

Baxter, at last brought to his senses, had ample time to realize, as he sat disconsolately in irons in the run, that he had made an utter fool of himself and that Captain Bill was a most kindly and humane man or otherwise he would have killed the ringleader of the mutiny. Each time he thought of his murderous attack on the skipper he trembled and felt faint to think to what lengths he had gone, and how, to satisfy a ridiculous grudge, he had practically thrust his neck into the hangman's noose, he was, in fact, a completely changed man, and when he was finally released he endeavored in every way to prove to the captain and mate that he was heartily sorry for the villainous part he had played.

"Reckon we won't have no more ructions aboard the old hooker,” observed Captain Bill, as, after the Endeavor had successfully rounded Cape Horn, he watched the crew working like beavers and bellowing chanteys as they spread sail after sail to the fair wind wrinkling the blue surface of the Pacific. "Didn't I tell you if any trouble started I was waitin’ halfway to meet it?"

Mr. Geer chuckled. "Reckon ye did, cap’n. But seems like to me ye didn't stop halfway. Not more'n quarter at most, I’d say. An' I reckon ye had 'bout all the fightin’ ye wanted for a spell. Guess that was as big a mix-up as ye’ll ever get mussed up in."

“Well, mebbe," agreed Captain Bill, chewing reflectively at his cigar as a smile of pleasurable remembrance flickered over his face. "But there ain't no tellin’. Howsomever, I’m still sayin’: I ain't never yet met up with nothin’ I can't lick."

But though neither Mr. Geer nor Captain Haven could possibly have guessed it. Fightin’ Bill's hardest battle was yet to come, and in a way that no one on earth could have dreamed.

With a willing, lively crew, with a contrite and efficient second mate, and with a steward who evolved most amazing and delectable dishes from the limited larder of the Endeavor, the old ship worked slowly across the Pacific toward the islands. Whales were plentiful, and rapidly the hold and 'tween decks of the Endeavor were filled with casks of oil and spermaceti.

But among the islands whales were scarce. Weeks drifted by without sighting a "blow," and at last Captain Haven abandoned the sperm grounds and headed north for the right whale grounds. Several small whales had been taken and all was going well when one pleasant morning the hail. "She blo—ows!" came floating down from the lookout in the crosstrees.

Quickly yards were swung, boats were manned and lowered, and with the captain's craft leading, they went dashing to the west toward the huge right whale lazily swimming just awash, a mile distant.

Heretofore there had been little trouble and few disasters in taking either sperm or right whales. Boats, of course, had been stove, men now and then had been bruised, or had had a few bones broken, irons had drawn and lines had been lost by whales sounding to such depths that necessity compelled cutting the lines. But there had been no man killed, none badly injured, and few whales had been lost. So, now, as the captain's boat bore down toward the whale's head, no one expected or looked for trouble.

But the whale before the captain's boat was of different mettle from those the Endeavor’s men had met heretofore. Before the boat was within striking distance, just as the harpooner rose with his heavy iron in preparation to heave the weapon, the whale brought its stupendous flukes thundering down, swung sharply to one side and reared its head high, as it trying to see what manner of puny creatures these were that were approaching.

"Port, hard aport!” ordered Captain Bill in a hoarse whisper, as he strained at the steering sweep.

It was too late. The whale had seen, and the next instant came with a rush like a destroyer straight for the tiny thirty-foot boat. Before the boat could be swung, before the men had time to realize their danger, the creature was upon them. The wave from his massive head swung the boat high, swerving it from his path, but as he dashed by he struck viciously with his flukes, striking the boat amidships, tossing it high, a splintered and shattered wreck, and flinging the occupants clear of the wreckage into the sea.

Almost instantly Baxter's and the mate's boat had reached the scene, and quickly the floundering men were drawn to safety. But Captain Bill was missing.

Speechless, the men gazed about, searching the waves for their captain, half expecting to see him floating dead or wounded. But there was no sign of him, and the men's eyes turned to the whale. Then a cry of fear and wonder came from their lips. Swimming, struggling in the sea, Captain Bill was striving by every effort to avoid the infuriated whale bent on destroying his enemy. All knew that Fightin' Bill was a splendid swimmer. There was not the least danger of his drowning if left to himself. But to swim in the tossing maelstrom of water churned up by the maddened whale and to dodge the thrashing blows of flukes, the on-rushing mountain of head, was a superhuman task. Each moment the fascinated yet fear-filled men expected to see their captain smashed to bloody pulp by the monster.

Time and again the mates urged their boats nearer to the whale, hoping to get a chance to rescue the captain. But each time they were forced back, realizing that to draw closer would be merely to sacrifice the men, for the whale breeched, pike-poled, flung itself from side to side and lashed out with its enormous twenty-foot flukes, and to approach within reach of that hundred-ton mass of insane fury was suicidal.

Each time that Captain Bill seemed to have met his terrible fate, the watching men saw him again appear. Rearing his massive head, the whale would bring it crashing down like a descending avalanche upon the spot where the swimming man had been but a second before. But diving and dodging, Captain Bill avoided the blows. As the whale's head crashed down he would bob up a dozen feet farther back. Then, as the great flukes lashed up and outward he would vanish beneath the sea and reappear alongside the creature's head. He could not escape, could not swim for the waiting boats, for the moment he turned the whale would be upon him. Every sense, every ounce of his strength must be exerted to avoid the whale, and every watcher in the two boats realized fully that it was but a question of time before the captain's strength would give out and the whale would triumph. Already nearly three-quarters of an hour had passed. The captain seemed to swim more slowly, his dives were shorter, and all knew the end of the terrible, unequal combat was near.

And then an amazed cry from Mr. Geer broke the tense and breathless silence.

"By Judas!" he shouted. "Cap'n's a-tryin' to knife the critter!"

As the captain rose on a foaming wave, all saw the gleam of steel in his hand, and instantly his object dawned upon them. All knew that the tenderest spot on a right whale is the tip of the nose; all knew that the least injury, the slightest blow upon that spot will turn the most furious right whale, will drive the creature mad with pain. And now, avoiding the whale's rushes, keeping the position exactly in front of the whale where the huge beast could not see him, swimming slowly, silently, with upraised, gleaming sheath-knife, Captain Bill was approaching the whale's nose, an inch at a time.

Baffled for the moment, unable to see his enemy, the whale rested motionless, straining to catch some sound that would betray its enemy's whereabouts, or perhaps listening to be sure that enemy still survived. The next second Captain Bill was within arm's length of the great cetacean. The steel flashed up and down. High in air reared the whale's head, torrents of water streamed in cataracts from its body, flung half its length from the sea. With a thunderous stroke the great flukes struck the water, and, turning so quickly that he seemed to somersault backward, the whale raced madly to the north, crazed with pain from the captain's stroke, thinking only of escape.

Cheer after cheer arose from the anxious men's throats, and, bending to their oars, they fairly lifted their boats across the waves toward their victorious skipper, now struggling weakly and gasping for breath in the sea. Quickly they reached him. A dozen willing hands dragged his limp and bruised body over the rail of the mate's boat. Choking, sputtering, his breath coming in sobbing gulps, Captain Bill lay, half-drowned, in the bottom of the boat. But the little man was still game. Before the speeding craft was half way to the ship, Fightin’ Bill sat up and gazed a bit dazedly at the men and the troubled face of Mr. Geer bending over him. Then a wan smile widened his pale lips and creased the corners of his spaniellike eyes.

"Good God, captain, be ye much hurt?" cried the mate, with mingled fear and anxiety in his tones.

"Hurt? Hell, no!" spluttered Captain Bill. "But I'm dyin' for a smoke. Got a seegar 'bout you?"

Then, Mr. Geer, having fished a rather sodden and frayed cigar from his pocket, and the skipper, after some difficulty, having lighted it, he gave a self-satisfied sigh and leaned back contentedly against a line tub that had been placed against athwart.

"By Godfrey!" he exclaimed. "I said I'd never met nothin' I couldn't lick." he gasped “I never thought I'd have to lick a whale to prove it. And" he added as an afterthought, "you was way often your course when you said as how that scrap aboard ship was my biggest fight. Twan't nothin' to this. And, by Godfrey! I've had enough fightin’ at last to do me for some spell, and I reckon I'm entitled to a good, long lay-off. Blowed if I ain't!"

1 comment:

i must thank you for the efforts you've put in penning this blog. excellent blog post .

www.n8fan.net

Post a Comment