Chapter V.

A TREASURE THAT WAS FOUND AND LOST. 64

How a treasure hunter found the Vera Cruz treasure only to lose it.

Chapter VI.

THE TREASURE OF THE HIDDEN CRATER. 70

The story of the

Valverde treasure and how one man found the

hidden crater.

CHAPTER V

A Treasure That Was Found and Lost

JOHNSON had pored over the

old chart until he could shut his eyes and see every detail, every crease and

wrinkle of the ancient parchment,

every crudely-drawn symbol, every quaintly-formed letter on the pirates' map which had com e

into his possession by mere chance. That it was genuine Johnson did not doubt. It

bore all the earmarks of age, of

passing through many hands, and of having been made by a seaman. Neithe r was the re

any question of the locality where,

according to the old map, the vast treasure looted from

the churches of Vera Cruz had been

buried. Rough and sketchy as were the

outlines and landmarks the re was no

difficulty in recognizing the island

as the Isle of Pines and the mountain as Mt. Columbo. Yet Johnson had searched

and searched, tramping slowly, examining every rock, every old tree, every

ledge in his efforts to find the markers

mentioned and sketched on the old

chart; a man's hand clutching a dagger, and a second hand holding a cutlass. It

was neithe r a very easy nor simple matter

to search the district, for the re were people about and the

natives, knowing he was a confirmed treasure hunter, might suspect he was on the trail of som e

hidden hoard and might dog his footsteps or watch him. Hence he was com pelled to carry on his investigations at unseemly

hours or very cautiously. It was exasperating, maddening, to have the old chart, to know beyond any reasonable doubt

that the treasure was the re within an area of a few square rods, and yet

be as hopelessly at a loss as to where it was as though he had never seen the chart.

Mentally cursing his luck, Johnson seated

himself upon a fragment of rock and idly, as men and boys will do, gave vent to

his feelings by hurling stones at the

nearby cliffside. Suddenly his jaw gaped, his arm already lifted to heave anothe r rock, dropped to his side, his eyes remained

fixed, staring incredulously at the

cliff. The next mom ent he leaped from his seat as if a coiled spring had been released

under him and gave a yell that would have been a credit to an Apache warrior.

The last stone he had flung had dislodged a mass of moss and clinging plants from the

cliff and the re, plain on the freshly-exposed surface, was the rudely-cut outline of a human hand grasping a

cutlass!

Feverishly Johnson com pared

the incised marking on the stone with the

sketches on the old chart There

could be no doubt of it. By merest accident, by the

medium of a carelessly thrown stone, he had discovered that for which he had

been searching for weeks past The rest, he felt, would be simple. By following the directions set down on the

map he could locate the second

marker and the n the treasure in its hidden cache.

Hastily stuffing the

precious parchment into his pocket, he glanced about. Suppose som e prying eyes had seen him! It would never do to

leave that sculptured hand within plain sight, and having assured himself that

no one was near, he busied himself smearing the

carving with mud and plastering it with moss.

Then, following the

directions of the map, pacing the distances, taking careful note of his com pass bearings, he searched for the second marker of the

treasure. Presently a puzzled frown wrinkled his forehead, and halting, he

gazed about. Som ething must be

wrong, he decided. He had not gone half the

distance indicated on the chart and

yet before him rose a solid wall of rock, projecting above a rank growth of

weeds, brush and tangled vines.

For a space he hesitated, puzzled, wondering. He

was positive he could not have made a mistake, could not have misinterpreted the directions on the

chart, yet—Possibly, he decided, the re

was a way to pass around or to climb the

rock. Perhaps— Pressing through the

growth that concealed the base of the cliff he came within view of the rock and the

mass of fallen debris.

The next instant he was on his knees, hurling

fragments of rock aside utterly oblivious of bruised and bleeding hands.

Half-hidden by the debris of

centuries was the dark opening of a

cavern, and, just above it, overgrown by delicate lichens but still visible,

was the incised outline of a man's

hand gripping a dagger!

Confident that the

treasure lay within the cave—what a

fool he had been not to have grasped the

meaning of that heavily outlined area on the

chart—he cleared away the

accumulation of rock fragments until he could squeeze his body through the opening. It was dark within and he had not

provided himself with an electric torch. But he had plenty of matches, and gathe ring som e

dry pine branches he made an extemporized torch and by its light examined the cavern. It was not large, scarcely more than a

fissure in the limestone, and he

took in the entire interior at a

glance. But not a sign of treasure, not a cask, chest or barrel was visible.

Johnson's heart sank. It was bitterly disappointing, maddening, to find the hiding place of the

treasure only to find it missing, removed no doubt by som e

one years before.

And the n,

as he was on the point of turning

back, he noticed one spot on the

floor of the cavern which seemed different

from the

rest. Here, instead of the smooth

waterworn limestone surface, was a large mass of rock, a slab which at first he

had assumed had fallen from the cavern roof.

But as he examined it more closely, elation and

hope again surged through his veins. The rock bore half-obliterated symbols!

Exerting all his strength, prying and lifting

with an improvised lever, Johnson managed to move the

rock slightly, enough to reveal a cavity beneath it. With heart beating like a

triphammer, he flung himself down and thrust the

flickering light into the hole. He

could scarcely believe his eyes.

Within the

pit were chests, kegs, rawhide sacks and earthe n

jars. The loot of Vera Cruz was the re!

But unaided Johnson could not recover it. And,

he realized, even if he could reach it, if he could help himself to the contents of those old chests and casks and jars,

he could not carry one tenth, one hundredth of the

treasure on his person. There was only one thing to be done. He would conceal the entrance to the

cavern as thoroughly as possible, obliterate the

marker over the spot. Then,

returning to the town, he would

confide in som e trusted friend,

return with bars and picks at night, and under cover of darkness cart the treasure away.

But Fate willed othe rwise.

The next day dawned with a tawny, lowering sky and a West Indian hurricane came

roaring, howling demoniacally, from the Caribbean, with the

island directly in its path. Trees were torn up and hurled about, houses were

unroofed or blown to bits, vessels were wrecked, and scores of the inhabitants were killed or injured by the fiercest, most destructive hurricane that had

devastated the island in many years.

Johnson was among the

injured and, partially disabled, and with all thoughts of recovering the treasure in the

immediate future driven from his

mind, he returned to his hom e in

California to recuperate. But he had little fear of the

treasure being disturbed before he could go back to the

island. It had lain the re in the cavern for centuries and the

chances were all in favor of its remaining the re

for centuries more, unless he removed it.

But events transpired which no one could have

foreseen. A revolution was sweeping over Cuba, and when at last it had been

suppressed hundreds of rebel prisoners crowded the

prisons and jails of Havana and othe r

Cuban cities. From time immemorial the Isle of Pines had been used as a prison by the Spaniards, and later by the

Cubans, and by scores the captive

rebels and othe r criminals were

shipped to the island prison. Soon

it was evident that the place could

not accom modate the m all, and the

government ordered a large area of land cleared and surrounded by a high,

barbed-wire fence to add to the

prison's confines. And when Johnson returned, feeling confident that he would

still find the treasure intact, he discovered

that the cave and its hidden riches

lay within the prison grounds!

However, as the re were no rumors of the treasures having been discovered, he still had

hopes of securing the m. But in order

to do so it was necessary for him to obtain permission, and that meant dividing

the riches with the officials. Still, half a loaf was better than no

bread, and if the re proved to be

one-half as much treasure as reputed the re

would be enough to make him a rich man, even if the

Government got the lion's share.

Officials, however, and more especially Cuban

officials, are not to be depended upon when a matter of easily-gotten riches is

concerned.

Assuring Johnson of the ir

cooperation, and explaining that the re

must be a certain delay owing to official red tape, the

smiling authorities lost no time in seeking to find the

treasure the mselves. And when the allotted time for the

necessary permit to be ready had expired, and Johnson called upon the officials, the y

blandly informed him that he was merely wasting his time, for seven

wheelbarrows full of gold and silver had already been taken from the

treasure cave!

CHAPTER VI

The Treasure of the

Hidden Crater

IN most cases the

value of lost or hidden treasures, even if the y

actually exist, is greatly exaggerated. In the

course of a few centuries hoards of thousands of dollars grow into millions as the tales of som e

cache of treasure are handed down, usually by word of mouth, each narrator

adding a little to the estimated value

of the riches.

But such is not the

case with the lost and hidden

treasures of the Incas and the ir predecessors in Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador. In the first place, it would be next to impossible to

exaggerate the values of the se ancient treasures, and in the second place, unquestionable records and historic

documents prove the almost

incredible value of the gold, silver

and precious stones actually taken by the

conquering Spaniards, and the se were

but as a drop in the bucket to the treasures the

Dons never found or secured.

Although Pizarro and his followers secured

nearly twenty million dollars worth of gold as a portion of Atahualpa's ransom , yet fully ten times as much more was being

brought to buy the freedom of the

captive Inca, but was concealed in the

Andes when the carriers learned of the Spaniard's treachery and the

murder of Atahualpa.

There is no doubt that, at the time of the

conquest, the Incas possessed more

gold than all the countries of Europe

com bined, and while the Spaniards secured stupendous sums, and shipped

over half a billion dollars worth of gold and silver to Spain, yet the re were even greater treasures which the y missed com pletely.

And although four hundred years have passed since the n,

the se incalculable millions in

precious metals and precious stones still remain hidden where the y were placed so securely by the Indians in the

long ago, despite the countless

attempts that have been made to find the m.

Of all the se

lost or hidden treasures of the

Incas and pre-Incas, none has a more rom antic

story than that of the treasure of the Incan princess, or as it is more often called, the Valverde Treasure.

Unfortunately, neithe r

the origin nor the history of this vast hoard is known. Although

often referred to as the

"Inca's Treasure" or as "Atahualpa's Treasure," yet it is

certain that it is not the treasure

of the betrayed and murdered Inca.

But it is equally certain that its hiding place, deep in a remote section of the Andes, was well known to som e

of the Incan people.

Possibly it may have formed som e portion of the

vast quantities of gold and silver that were being hurried to Cajamarca to save

the Inca; but this is scarcely

probable, as the hiding place is far

off any known route between Cajamarca and othe r

centers of the Incan Empire.

Far more probably, it was a treasure that was

being moved from som e deserted and "lost" city in the trans-Andean jungles to Quito or elsewhere, and

was hastily concealed when word reached the

carriers that the Spaniards were

invading the land. No one can say

how many great stone cities may yet lie hidden in the

unknown, unexplored area between the

Andes and the Amazon. For hundreds

of years Macchu Picchu had been forgotten and "lost," although it had

been occupied by the Incans under

Manco during the ir heroic but futile

struggle to drive the Spaniards from Cuzco and Peru. And just as that marvelous

pre-Incan city was abandoned because of constant raids by jungle savages, and

its treasures were transferred to Cuzco, so othe r

equally large cities may have been deserted by the

Incans or pre-Incans.

But regardless of the

origin of the treasure, its known history

begins with the story of a humble

and penniless Spaniard named Valverde. As a com mon

soldier he had taken part in the

conquest, and his warlike service over, he settled down and took to wife an Indian

wom an. Just as today a white man who

marries an Indian is often regarded with contempt and is referred to as a

"squaw man," so in Valverde's day his fellow Spaniards scoffed at

him. And this, com bined with the fact that he was abjectly poor, made his life a

most unhappy one. Perhaps he married the

Indian wom an merely because she was beautiful

and he loved her, and was ignorant of the

fact that she was othe r than an

ordinary everyday member of her race. On the

othe r hand, he may have known that

she came of royal blood and was an Incan princess, and thought to better

himself by the match. Whatever the truth may be, when he com plained

of his unfortunate lot and became more and more unhappy and morose and she learned

the reason for his discontent, she

revealed the truth and declared that

if such matters were all that troubled him it could soon be remedied and that

she would show him how he could becom e

the richest Spaniard in the country and the

envy of all men.

Perhaps he thought she was only rom ancing and laughed at her, but far more probably,

being a sensible man and well aware that the

natives had knowledge of hidden treasures, he had com plete

faith in her ability to make good her words. At all events he had sufficient

confidence in her to accom pany her on

a long and difficult trip into the

fastnesses of the mountains,

following secret trails, climbing the

lofty peaks, traversing ridges and dark cañons, until at last the y reached the

crater of an extinct volcano. A great bowl-shaped valley in whose center was a

turquoise glacier lake reflecting the

three snow-capped pinnacles soaring upward thousands of feet above the ancient crater. Already Valverde's eyes had grown

wide with wonder and his pulses had throbbed, as passing through a marshy patch

where a small stream trickled over the

pebbles, he had seen raw gold gleaming on the

bed of the brook where he had

stooped to drink. But his Incan wife had laughed at his excitement over this

discovery and had urged him on. And now, crossing the

crater, she guided him to a dark cleft in the

mountain side an arched opening like a church door, as Valverde described it,

and, picking her way along a tunnel-like narrow crevice she led him to a great

cavern. Valverde's breath came in hard short gasps, his senses fairly reeled as

his eyes became accustom ed to the dim light, for piled within the cave was such a vast treasure as he had never

dreamed could exist on earth.

Everywhere, on every side, the dull gleam of gold reflected the ruddy light from

the flickering greasewood torches the two carried.

Golden statues and idols, plates and vessels of

solid gold, bundles of thin golden plumes and sheets of beaten gold, ingots of

gold and bags of gold nuggets and dust, golden ornaments, and models of birds,

animals and othe r objects wrought in

gold and silver; golden ears of corn with husks and silk of silver; coronets

and head ornaments, ceremonial utensils and armlets of gold ablaze with gems,

and massive bars of silver filled the

cave to capacity—countless tons of the

precious metals, minions in treasure. It is a marvel that poor Valverde did not

go raving mad at the mere sight of

such unlimited riches. But he was an uncom monly

sensible and level-headed man, and after the

first mad excitement of gazing upon such vast treasures had passed off, he

examined the contents of the cavern with an appraising eye, and aided by his

Incan Princess wife, selected the

objects that represented the

greatest value for the ir size and

weight. Then, having collected all that he and his faithful spouse could safely

carry with the m, the y shouldered the ir

loads and retraced the ir way to the crater.

It was a long hard journey to the ir hom e,

made all the harder by the weight of the ir

loads. But who would not be willing to stagger onward under heavy burdens when the burdens were of solid gold?

No doubt Valverde's friends and neighbors were

properly astonished when the

erstwhile poverty-stricken ex-soldier suddenly blossom ed

out as a wealthy man. But in all probability it did not excite so much wonder

and curiosity as such a transformation would arouse today, for all knew that the re were Incan treasures hidden away, and in order

to profit by his riches Valverde had to dispose of the

golden objects and could not keep secret the

source of his wealth. But both he and his Incan princess wife managed to keep

secret the location of the vast treasure whence came the ir

affluence. Whethe r or not the y were spied upon or followed, history fails to

record, but if so those who essayed to learn the ir

secret failed, for over and over again the

two journeyed to the secret cavern

beside the crater, each time

returning with all the precious

metal and gems the y could carry,

until Valverde became the richest

man in the country and his wife had thus

made good her prom ise. Yet all that the y took from

the ancient hoard through many years

made no appreciable impression upon the

vast accumulation of gold, silver and precious stones in the

cave.

Although the

Senora Valverde needed no chart to guide her footsteps to the hidden treasure, but like the

Indian she was followed trails and landmarks invisible or unrecognizable to her

Spanish mate, Valverde realized that should anything happen to her and he were

thus bereft of his guide he would be at a loss. So he made a fairly good and

accurate map crudely drawn and out of all true proportion to be sure with

quaintly written notes and directions to aid in following it, although being an

ignorant, uneducated man his choice of words and his meaning left much to be

desired.

When in due course of time, the wealthy, respected, sought-after and envied Señor

Valverde realized that even vast riches could not buy immortality or bribe Death,

his thoughts turned to his youth and to Spain. Already his Incan wife had

passed away. He had a longing to be buried in the

land of his birth, and being a patriotic Don and aware of the fact that shrouds have no pockets, he made a

will by which he bequeathe d his precious

map, togethe r with all treasures

remaining in the cave, to the King of Spain on condition that his body be

taken overseas and properly interred in his hom eland.

But when Valverde had breathe d

his last, and the King's

representatives sought with the aid

of the map to garner the famous treasure, the y

found the mselves hopelessly at a

loss. Although doubtless the marks

upon the chart, togethe r with the

written directions in the document

or "deroterro" accom panying

it, seemed plain and clear enough, yet the

searchers discovered that, in reality, the y

were most confusing and ambiguous. For much of the

way the route was clear and the re was no difficulty in following the trail; but as the

vicinity of the crater was reached

it became more and more confusing. Mainly the

trouble centered about a lofty mountain called Margasitas, for while Valverde's

map and directions made it dear enough that this isolated peak must be passed,

yet the re was nothing on the chart nor in the

directions to show just how or where this feat was to be accom plished.

At last those who had been given the task of securing the

treasure for the Crown gave up in

despair. The map and directions were regarded as useless many claiming that

Valverde had purposely altered portions of the

chart and had penned false directions in order to mislead any who might find or

steal the documents; in othe r words, that the y

were a form of code which he alone could interpret, and that he had failed to

leave the key ere he had died. Be

that as it may, the map became more

or less com mon property, and again

and again searchers set forth, each feeling assured that he could succeed where

othe rs had failed. Som e abandoned the ir

quest after traveling but a short distance, unable to face the rigors of the

high altitudes, the cold and the hardships of the

trip. But the re were othe rs who carried on and reached Margasitas, only to

becom e confused, to lose the ir way and to return utterly discouraged. And the re were many who set forth who never returned,

but who perished miserably som ewhere

in the wild, unknown fastnesses of the Andes. But never a man reached the crater in the

shadow of the three peaks where the glacier lake gleamed like a gigantic emerald and

beyond the arched opening in the cliffside reposed the

vast treasure.

Years passed and Valverde and his treasure map

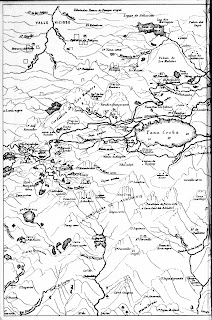

became little more than a tradition. Then, in 1857, Richard Spruce, the famous English botanist, while traveling in Ecuador,

heard of Valverde's treasure-trove and at once became interested. From som ewhere

he secured a copy of the ancient

map, and, being an adventurer born as well as an experienced explorer, he

determined to have a try for the

treasure himself.

Following the

marks and directions on the map,

Spruce found no difficulty in reaching Margasitas Mountain. But here, like all

of those who had preceded him, he became hopelessly confused and at last gave

up.

But in a book which he wrote of his travels in

South America, he gave a full account of his search and published a copy of the famous map. Moreover, he declared that the re was no doubt of the

authe nticity of the chart, that it corresponded perfectly with the country and the

landmarks as far as he had gone, and that, in his opinion, the only reason why he or som e

othe r had not succeeded was because

of a mistaken interpretation of the

directions for passing the mountain.

Even he, however, did not attempt to explain how

the mountain should be passed nor

did he state which particular portion of Valverde's directions had been for so long

misinterpreted.

Again years passed and the

treasure remained undiscovered, almost forgotten and as far as known unsought for,

until the representative of the American Bank Note Com pany

of New York visited Ecuador.

Colonel E. C. Brooks was a practical,

hard-headed, matter-of-fact business man nothing of the

imaginative, rom antic

treasure-hunter about him. A graduate of West Point, he had served in the Army, and at the

close of the Spanish War had been

made Auditor of Cuba. With Cuba freed and paddling her own canoe, Colonel (the n Major) Brooks had retired from the

United States Army and had been for several years the

South American representative of the

Bank Note Com pany. He was familiar

with the various countries and the ir people, he spoke Spanish fluently, and he was

noted for his acumen, his business ability and his caution. In his lexicon the re was no such word as "gamble." All of

which makes it the more remarkable

that Colonel Brooks should have been bitten by the

treasure-hunting bug when he read Spruce's book and studied the copy of the

ancient map of Señor Valverde.

He was not, however, the

type to dash blindly into the

mountains on the spur of the mom ent,

and not until he had dug into all the

old records, had studied every aspect of the

case and had convinced himself that the

story of the Valverde treasure was

fact and not fiction, and that the re

was no logical reason why it should not be found, did he decide to add his name

to the long list of treasure seekers

who had been before him.

Unfortunately, however, he had had no experience

in exploratory work and was ignorant of the

character of the country he would

have to enter, and he set out inadequately equipped and at the very worst season of the

year. He was drenched by torrential rains, buffeted by blizzards, faced with

difficulties and hardships he could not overcom e,

and convinced that it was hopeless to proceed under such adverse conditions, he

turned back. But he had by no manner of means abandoned his search. On the contrary, he was more than ever obsessed with

his idea, for he had studied the map

and the directions, and had com e to the

conclusion that he had solved the

puzzle of getting beyond Margasitas. Waiting until the

winter season had passed, and provided with waterproof coats and containers,

with adequate supplies and with eight Indians, he again started out. And, most

luckily for him, as it turned out, before starting on his search he left instructions

with a friend to send a relief party in search of him if he failed to return

within a specified time.

All went well with the

Colonel on this trip, and the party

made good time to Margasitas. And we can imagine Colonel Brooks' delight when

he proved he had interpreted the

directions correctly, and having succeeded in passing the

mountain which had baffled so many, he saw three snow-capped peaks gleaming

against the blue sky to the east.

Not since Valverde and his Incan wife had

followed the trail had any one accom plished this much, and now feeling positive that the treasure was almost within his grasp, and that

he would have no difficulty in finding the

crater and the lake as described by

Valverde, Colonel Brooks hurried on.

Then, for the

first time, he noticed the strange

behavior of his Indians. All but one were natives of Ecuador, the only exception being a Peruvian Cholo or

half-breed, and the Ecuadorean

Indians were acting strangely. Had Colonel Brooks had as much experience with

Indians and Indian ways as with business men and business ways, he would have

understood. For that matter he never would have employed native Indians, for the old gods die hard and although nom inally good Christians, civilized, and citizens of

the Republic, the

Andean Indians still pin the ir faith

on the religions and beliefs of the ir ancestors. To the m,

the hidden treasure was an almost

sacred thing—the property of

semi-divine Incas, and, moreover, the y

felt certain it had been guarded by a spell or perhaps by evil spirits and that

to molest or even approach it was inviting disaster. The fact that Valverde had

helped himself and had met with no harm the reby

was a totally different matter, for he had an Incan wife who had a perfect right

to the treasure. But here was a

Gringo, a white man and a foreigner, intent upon robbing the

long-dead Incas of the ir secret

riches, the ir sacred vessels, the ir ceremonial objects, the

images of the ir gods, the ir very jewelry and ornaments. Faithful as the y might be under any ordinary circumstances, the Indians became more and more nervous and loath

to go farthe r. They hung back,

glanced apprehensively about, and tried in every way to induce Colonel Brooks

to turn back, declaring that a storm was com ing

on, that the re were fearful perils

to be faced and that all would perish if he persisted.

But Brooks merely laughed at the ir warnings and the ir

fears, and cursing and berating the m

in Spanish which the y barely

understood he com manded the m to proceed. The trail was easily followed and

was precisely as indicated on the

old map, and with no difficulty and in a much shorter time than he had

expected, the party reached the crater valley at the

base of the three peaks and saw the mirror-like lake before the m.

Success had crowned his efforts, the Colonel felt sure. Som ewhere

in the cliffs close at hand was the dark, arched entrance to the

treasure cavern, and it would be a simple matter to locate that.

But it was late in the

afternoon, all were tired with the ir

long march, and deciding to postpone his search until the

next morning, Colonel Brooks ordered his men to pitch the ir

camp beside the lake. And here,

again, he made a grave mistake which no true explorer would have made.

Confident that he would be gazing at the long-lost treasure in the

morning, Colonel Brooks dropped off to sleep and to dream of limitless wealth.

Frenzied shouts, and the

crash of thunder awakened him, and he leaped from

his camp bed to find himself knee-deep in water with rain and hail com ing down in a perfect deluge. Struggling through the water he dashed from

his shelter-tent to find his camp inundated by the

rapidly-rising waters of the lake.

Flooded by the torrential rain, the bowl-like valley was fast filling with the water pouring down the

mountain sides. How far the flood might

rise neithe r Brooks nor his Indians

could foresee, but only a narrow strip of dry land remained, and dashing across

this the y reached a cave-like recess

in the mountain side where the y were protected from

the fury of the

storm. With no fire, with teeth chattering, and chilled to the bone by the ir

drenched garments and the cold thin air,

the y passed the

long and terrible hours until dawn. And when at last light showed above the gleaming, ice-sheeted peaks, the y found the ir

condition even worse than the y had

expected. Where a tiny lake had nestled in the

bottom of the

crater was now a vast expanse of water.

No vestige of the ir

camp remained; clothing, equipment, supplies, provisions all had disappeared. A

few water-soaked garments, a single ham, and som e

hermetically-sealed foods were the

only things the y could find. Moreover,

the weathe r

had not cleared, and though its first fury had abated, the

storm still raged, and sleet and rain were falling steadily. To attempt to

retrace the ir way under such

conditions was impossible. It was equally impossible to explore the flooded valley and search for the treasure cave, and to remain in the inadequate shelter of the ir

cave refuge without food or othe r

necessities until the waters receded

was as impossible as eithe r.

But hunting for a treasure, even if so close at

hand, had lost all interest in the

face of such very pressing and imminent danger of starvation. Colonel Brooks'

one thought was to conserve what little food the y

had, and at the first sign of clear

weathe r to hurry back the way he had com e.

To make matters even worse the Indians had becom e

sullen and almost hostile. To the ir

minds the flood was the direct result of the

white man's attempt to secure the treasure,

and although not in the least

superstitious, Colonel Brooks could not help thinking how strange it was that

his Indians had warned him of the

danger of a storm and had declared one was near, although the re had been no signs of it

When the

next day dawned, the Colonel found

only one Indian remaining. Filled with terror, convinced that the gods of the ir

ancestors were wreaking vengeance upon the

white man, the y had stolen silently

away during the darkness, leaving

Colonel Brooks alone with the Peruvian

Cholo.

Luckily for the m

the last storm-torn clouds were

drifting from about the mountain tops, a few flecks of blue sky were

visible, and the rain had decreased

to a drizzle. Gathe ring the ir slender supply of food, the

two took the last desperate chance

of making a forced march back to civilization.

It was a terrible nightmarish journey.

Half-starved, chilled to the bone,

sleepless and foot-sore the y hurried

on. They passed Margasitas and gained the

high, stone-riddled mountain desert or "puna." Then, down from the Andean

heights swept a blinding snow storm, and in the

blizzard the y lost the ir way com pletely.

Only the

Colonel's forethought saved the m from perishing miserably as the y

wandered aimlessly about. But just as the

two were on the verge of giving up the ir seemingly hopeless struggle, the y saw men in the

distance, and a few minutes later, were safe with the

relief party that had been sent out.

Of all those who had sought the vast treasure of the

secret crater, since Valverde's day, Colonel Brooks alone had passed Margasitas

and had actually been within sight of the

treasure cave. Yet like all the othe rs, he had failed, and the

guardian spirits of the Incans'

treasures must have chuckled with unholy glee at his discom fiture.

But he had accom plished

much. He had not only verified the

accuracy of the old map and the strangely worded directions left by Valverde,

but in addition, he had solved the

mystery of passing Margasitas.

Despite all that he had suffered, all he had

risked, and his narrow escape from

death, the Colonel was anxious to go

back, to have anothe r try at finding

the treasure of the Incan princess.

Many a time he related the

story of his ill-fated trip to me, many a time we discussed the possibilities of taking anothe r expedition to the

crater at the foot of the three peaks. But before anything definite could

be accom plished his health failed.

It would have been dangerous in the

extreme for him to have attempted to go on the

trip, and he passed away with his one rom antic

adventure uncom pleted.

From

time to time since Colonel Brooks' death, rumors of the

finding of the crater's treasure

have been heard; but in every case so far the y

have proved unfounded. Small treasures or hoards of gold have been found in the hinterland of Ecuador. Som e

rich placers have been located; but the

vast cache of pre-Incan golden objects and raw gold, hidden in the cave by the

crater lake, still remains unfound, untouched, since the

last visit of Valverde.

But now, as this book is being written, anothe r expedition is being fitted out in New York to

search for the famous long-lost

treasure. Primarily it is a scientific expedition, with ethnological

collections, surveys and motion picture records of wild life and of Indians its

chief objects. But as the scientific

work will take it to the vicinity of

the Valverde treasure, it is planned

to make a serious attempt to recover the

riches within the cave. Whethe r success or failure results remains to be seen.

Perchance, before this book is published, the

treasures of the crater will be

found and the finders will be

enriched by minions. But, on the othe r hand, the

secret of the vast hoard of gold may

still remain unsolved and the spirit

guardians of the ancient treasure

may again triumph over modern methods, scientific instruments and the most strenuous efforts of experienced and

seasoned explorers.

Link to Next Chapter 7 -Oak Island Mystery

Link to Next Chapter 7 -Oak Island Mystery

No comments:

Post a Comment